On Nov. 6, 1869, Rutgers beat the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), 6-4. Fall Saturdays haven’t been the same since. Today, 150 years after that first college football game, the sport brings together millions, as much for what happens off the field as for what happens on it. We love the parties as much as the passes, the hijinks as much as the handoffs. Players come and go, but one thing remains constant: fans coming together as one. Here, we celebrate these gatherings with snapshots of four distinct traditions that reflect our passion. So pull on your alma mater’s jersey and grab your favorite snack, because the games are back. And, more important, so are your people.

The Party

Sailgating, University of Washington, Seattle

If you love tailgating, you should try sailgating. Only a precious few college stadiums are situated where boats can host pregame parties. And none can match the ambiance at University of Washington games. With the majestic Cascades in the distance, boaters gather outside Husky Stadium on Lake Washington and take in one of the most picturesque views in college football.

About 150 boats can dock in Lake Washington’s Husky Harbor, with others floating farther from shore. Scott Grimm, whose family has been sailgating for 65 years, typically arrives at his spot at noon on Friday. And what a spot it is. When the sun rises, the purple sky matches the local uniforms. And when the sun sets behind the mountains, the sky erupts in a blaze of orange and yellow. Throw in the festive atmosphere, food, and drinks and, Grimm says, “It’s party central.”

Entering this season, since 1954, a Grimm boat has been docked in Husky Harbor for every game but one. (A family event a few years ago couldn’t be skipped or rescheduled.)

Grimm’s grandfather, Huber “Polly” Grimm, was the first All-American on Washington’s football team (1910). Grimm’s dad, also named Huber, attended Washington for one year; later, he graduated from Seattle University and went on to become a doctor for their athletic teams. Scott and all eight of his brothers also attended Seattle—which doesn’t have a football team. “We have divided loyalty,” he says, “[but] we bleed purple and gold in football.”

Onboard Grimm’s 54-foot Chris Craft Conqueror, guests feast on burgers, hot dogs, steaks, chili, and ribs, but they know to save room for Grimm’s famous grilled salmon, cooked on a cedar plank to medium-rare perfection. The boat holds up to 45 people, and Grimm will welcome anybody.

Well, almost anybody. Don’t request permission to board if you’re wearing Oregon Ducks gear.

Photo: SGM Stephan Engel

The Pageantry

Gametime Skydiving, U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York

At army football games on West Point’s campus, the most impressive touchdowns occur before kickoff. That’s when elite student members of the West Point Parachute Team jump out of a helicopter at 3,500 feet and deliver the game ball by landing on the field at Michie Stadium.

Of all the pomp and pageantry that surround college games, Army’s skydiving is one of the few rituals that carry real danger. Thomas Rounds, who graduated in May and commissioned as a second lieutenant, was the cadet in charge of the team last year. He made 635 jumps, practicing endlessly to achieve every soft landing.

At Michie Stadium, that’s no gimme. The venue has none of what parachutists look for in a good landing spot. It’s surrounded by a parking lot, woods, a road, and a reservoir; the light poles and goal posts reach out like bony fingers that can snag open chutes. A good landing starts with a good jumping location. The pilots and team study the wind speed from the time they gather at 5:30 a.m., and team members usually test the wind firsthand with a practice jump into the stadium and another into a pregame parade.

When the helicopter is in place for the game ball jump, the jumpmaster nods at the cadet and point out the door. Cadet Rounds would stand, salute the pilot, and leap. After free falling for five seconds, he would reach with his right hand to the small of his back and open the pilot chute. A few seconds later, after the canopy opened, Rounds would calculate his speed, the wind’s speed, and his position relative to the stadium, so he could steer himself to the target—some jumps start as far as a half-mile from Michie.

At first, Rounds would hear only wind. But as he would cross the 1,000-foot mark, crowd noise became audible. “You start to hear this dull roar,” he says. “It really picks up as you get closer and into the stadium. That’s when you’re like, Whoa, this is happening. That’s when I start to feel like I’m part of the experience.”

Early on as a jumper, he was vaguely aware an announcer was saying his name and hometown (Anoka, Minnesota) as he neared the ground. Last season, he could quote the person almost verbatim. That’s what 635 safe landings will give you.

Photo: Cassie Stricker

The Pep

Yell Leading, Texas A&M, College Station, Texas

The 102,733 fans who cram themselves into Texas A&M’s Kyle Field for football games do not have to be enticed to make a lot of noise. They rank among the loudest in the country, creating the rough equivalent of listening to a chain saw fighting with a Metallica concert.

But to kick that cacophony up another notch, Texas A&M uses yell leaders, a tradition of loud and proud ambassadorship more than 100 years old. At Aggies games and other university events, a yell is a chant that everyone knows, and yell leaders are like cheerleaders, motivational speakers, and singalong leaders all rolled into one. Though don’t dare call a yell a cheer. Volume is critical. Attend the famed Midnight Yell Practice on a Friday night, and you’ll learn all about “humping it,” leaning forward with your hands placed above your knees so you can better project your voice.

As head yell leader, Karsten Lowe takes deafening decibels and molds them and channels them, all to help spur the team on to victory. From his spot in the end zone in front of the student section, Lowe, wearing the yell leader’s traditional all-white uniform, keeps one eye on the game and one on the crowd. He and the other four yell leaders, all of whom are elected by the student body, act as a conduit connecting the players to the fans, and Lowe sees a symbiotic relationship between the 12th Man (the storied nickname given to the student section) and the 11 Aggies on the field.

“The players feed off the energy of the fans, and the fans feed off how well the players are doing,” he says. “I’ve talked to some of the players. They say how the fans participate, how they interact, will somehow help make a difference in the game.”

Picking up on nonverbal cues, Lowe reads the crowd and the game, trying to figure out the best yell to use. If fans are mad about a bad call, he’ll use hand signals called “pass-backs” to indicate to his fellow yell leaders and the crowd that he wants them to do a fan-favorite yell called “Beat the Hell.” If the other coach gets uppity, Lowe will pull out “Sit Down, Bus Driver.”

And then there’s “Horse Laugh,” used good naturedly if also nonsensically to put opponents in their place.

“Riffety, riffety, riff-raff!

Chiffity, chiffity, chiff-chaff!

Riff-raff! Chiff-chaff!

Let’s give ’em a horse laugh:

Sssssss!”

Sssssss? Huh?

“We don’t boo,” Lowe says. “We’re far too classy for that.”

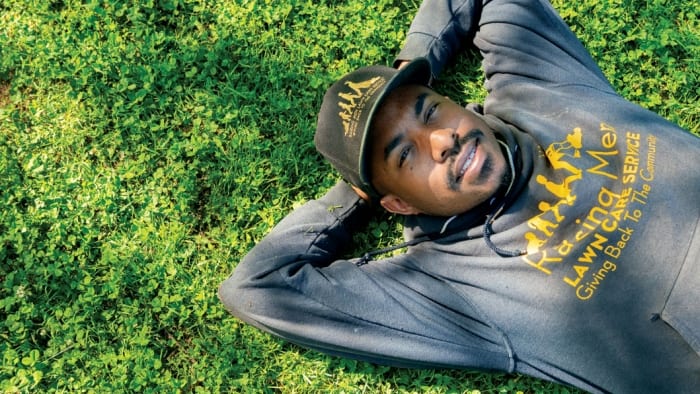

Photo: Carlton Hamlin/Grambling State University Media

The Performance

Playing at Halftime, Grambling State University, Grambling, Louisiana

Before halftime at Grambling State games, Lexia Thomas, piccolo in hand, walks to her place behind one of the end zones. Her heart pounds in her chest. “It’s like the first time, every time,” she says. Adorned in her wool uniform—warm enough anywhere but hotter than a boiled crawfish in the Louisiana heat—she gives herself a reminder: “Breathe.” And for good reason: She’s about to play for thousands while going through a workout worthy of a running back.

Few college football bands get—or deserve—as much attention as Grambling State’s. With routines that are part concert, part dance show, and all energy, the Grambling State World-Famed Tiger Marching Band, founded in 1926, has performed for Super Bowls and state fairs, Barack Obama and Beyoncé.

The choreography itself can be dizzying. One move, known as “Breakdown,” involves hopping on one foot, and then jumping off two feet, spinning 180 degrees, and then repeating that, gyrating throughout. The season culminates with the Bayou Classic, the annual showdown between Grambling State and Southern University, where the competition between bands is arguably fiercer than the football game itself. The first time Thomas, a senior this fall, played that event, she couldn’t believe she was there. It’s the Carnegie Hall of college football marching band shows, and as she stood on the field, she thought, Am I really a part of this?

But no matter the game, once the band begins, Thomas’ nerves fade. Her concentration on the notes and the moves is so complete that she becomes unaware of the world around her. The aura the band produces, though, is unmistakable.

“The band creates the atmosphere at games,” she says. “It gives [the fans] that extra college feel. Even the football players ask us to play certain songs to get them hyped on the field. They might end up scoring a touchdown because we played a certain song.”

Thomas is a math and physics major, and her performance rolls her coursework into an exuberant explosion of controlled chaos. Music is the application of fractions—whole notes, half notes, quarter notes—and a halftime show is physics come to life, a harmonious formula of angles, spatial relationships, and timing.

When the show ends, she begins to notice the crowd again and hears the chant: “G-S! G-S-U!” She looks up and tries to judge from fans’ expressions how the show went. Are they standing, smiling, clapping, yelling? If yes, then all the pressure to perform, all the hours of practice (during the summer, it begins at dawn and ends at night) become worth it. Has the crowd ever not reacted that way?

“I haven’t experienced it,” she says.